On Oct. 15, 1937, my father crossed the border from Kehl, in the southwest corner of Germany, into Strasbourg, France. His German passport was stamped with a 15-day transit visa to attend l’Exposition Internationale in Paris, an event devoted to “art and technology in modern life.” The exposition featured pavilions from 44 countries, notably a muscular Soviet tower crowned by a monumental statue of a male worker and a female peasant triumphantly thrusting a hammer and sickle into the sky, which stood directly across the Trocadero from a menacing German monolith topped by an eagle and swastika designed by Nazi architect Albert Speer. The event attracted more than 31 million visitors, but whether my father was among them is not clear.

Dad’s older brother, Ernst, had immigrated to France several years earlier, but whether the two brothers were able to meet is also not clear.

Dad’s U.S. immigration visa.

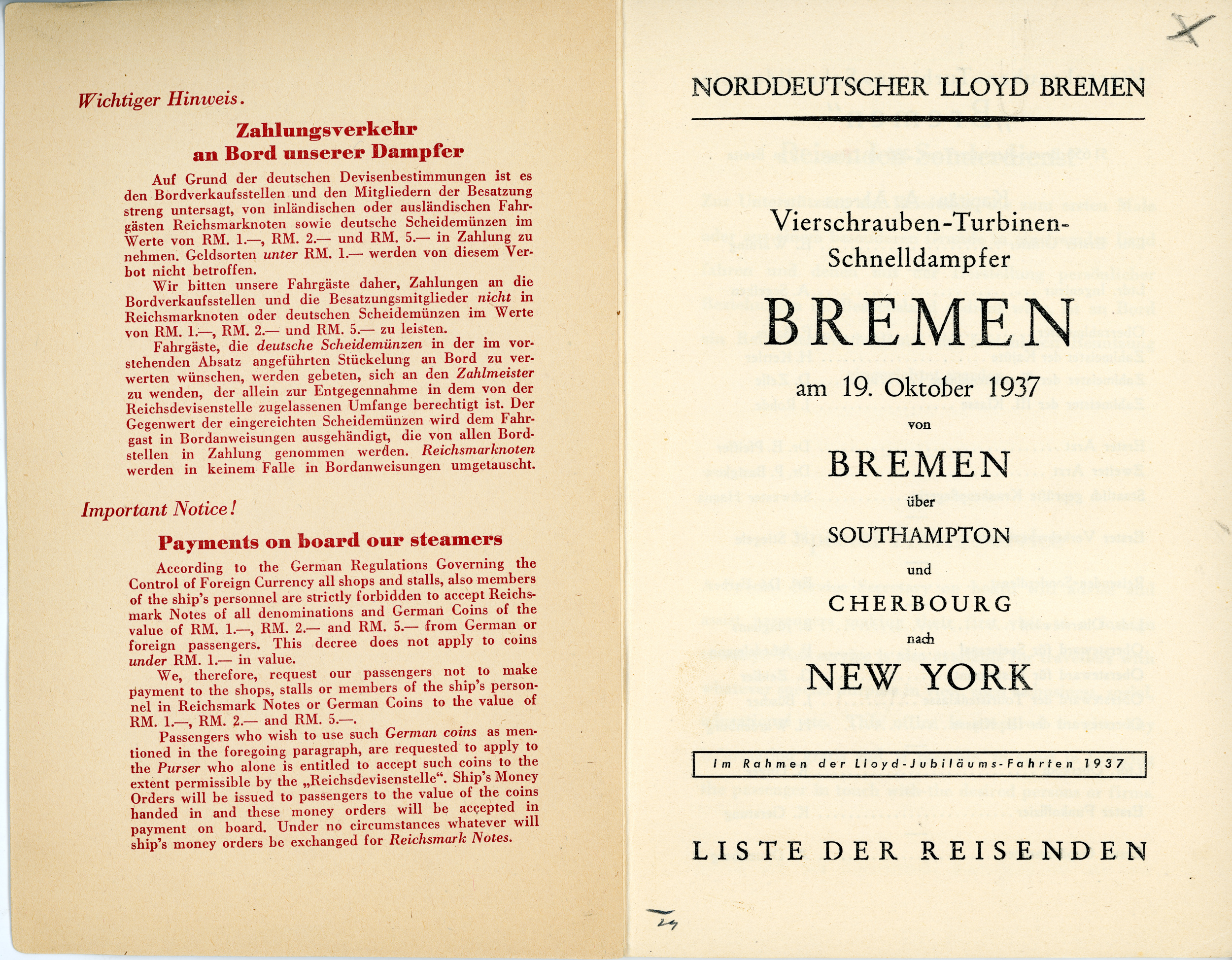

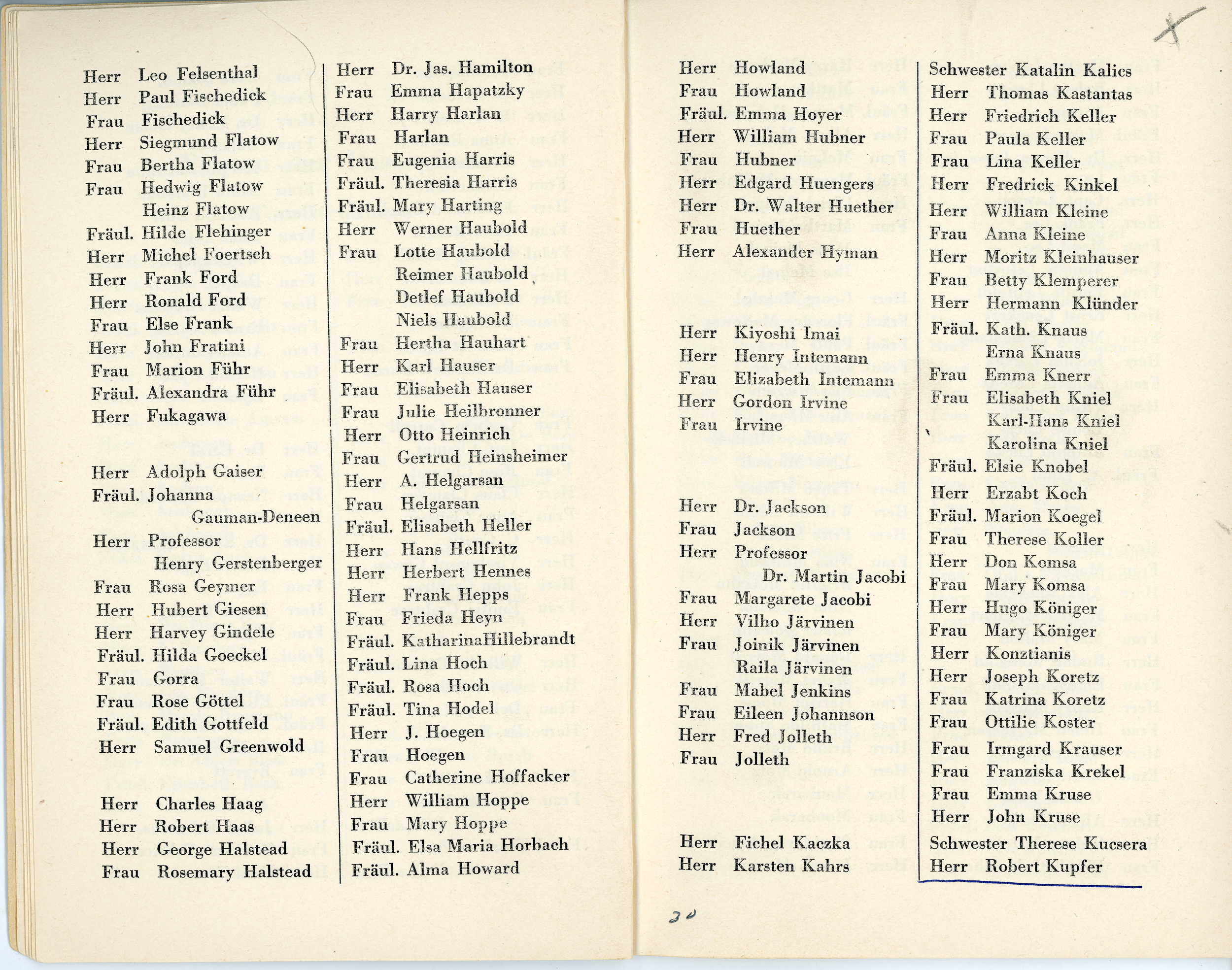

My father was carrying an American visa stating he was “quota immigrant” number 13,020. The visa quota for German residents in fiscal year 1937-38 was 27,370, but only 18,148, or 66 percent, were actually issued, most of them to Jews. The disparity reflected Washington’s strict immigration policies at the time. (U.S. officials were even stingier the previous year, when only 12,532 visas were issued to Germans, 48 percent of the annual quota.) Five days after entering France, on October 20, my father boarded the SS Bremen in Cherbourg for the five–day voyage across the Atlantic to New York. The Bremen, the jewel of the German merchant fleet, was one of the swiftest and most luxurious ocean liners afloat. On her maiden voyage in 1929 the sleek, bulbous-bowed ship captured the coveted Blue Riband for the fastest Atlantic crossing, a distinction that had been held for nearly 20 years by Cunard’s Mauretania.

Although German shipping lines had an express policy of downplaying Nazism, the Bremen’s crew of more than 900 men and a few women included a Nazi Party cell and a unit of the SA, Hitler’s brown-shirted storm troopers. The luxury liner had been the target of several anti-Nazi demonstrations while she was docked in New York, including one on July 26, 1935, in which Communist protesters stormed the ship and ripped down the swastika flag fluttering from her stern, tossing it into the Hudson.

The Bremen steamed into New York Harbor on Monday, October 25, slipping past the outstretched torch of the Statue of Liberty on her port side and tacking toward the phalanx of skyscrapers ringing Lower Manhattan. As she made her way up the Hudson and slowly swung into Pier 86 in Midtown, the needle-nosed spire of the Empire State Building and, beyond that, the terraced crown of the Chrysler Building shimmered in the distance.

SS Bremen depicted on a German postage stamp / Bremen passenger list, October 1937.

When he stepped off the gangway at the Hudson River piers, Dad was greeted by Sigfried Herrmann, an elderly uncle of his mother through marriage. Herrmann, the youngest of eight children, was 16 when he immigrated to the United States in 1882 — long before my father was born — so it’s unlikely the two men had ever met before. Dad had a few other distant cousins and family friends scattered around the New York area, but other than that he was the proverbial stranger in a strange land.

He brought with him a trunk packed with an assortment of fine clothes — bespoke wool suits; monogrammed silk shirts; silk ties, handkerchiefs and ascots; Italian leather shoes; riding breeches and boots. Some of these items I have still, though I seldom have occasion to wear such fancy duds.

He also brought a red leather album, thick as the Manhattan telephone directory, containing his stamp collection; a small Zeiss Ikon folding camera (which today sits on the bookcase in my living room); a pair of Zeiss binoculars in a brown leather case; a wristwatch, pair of garnet cufflinks, and a few other modest pieces of jewelry; and a violin in a velvet-lined case from his schoolboy days.

“ Tucked in his coat pocket was another item that would play a pivotal role in establishing his new life in America: a custom-made platinum cigarette case.”

Tucked in his coat pocket was another item that would play a pivotal role in establishing his new life in America: a custom-made platinum cigarette case. There were strict limits on the amount of money and other valuables Jewish emigrants could take out of Germany at the time. They were allowed to bring no more than 10 Reichsmarks, or about $4, and were restricted in the amount of funds they could transfer abroad from German banks. They were also required to pay an onerous emigration tax, called a Reichsfluchtsteuer. These measures, designed to drain Jews of their assets, had their intended effect: The vast majority of German Jewish refugees arrived in their new countries essentially as paupers.

The cigarette case had been made for the express purpose of circumventing those restrictions. Platinum is exponentially more valuable than silver — in 1937 it was worth $47 an ounce, compared with 45 cents an ounce for silver — but to the unschooled eye it can pass for its more quotidian cousin. Dad later sold the case for more than $2,000, a princely sum in those days.

Top: The German (left) and Soviet pavillions at l’Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne in Paris. Photolith, 1937.

Robert and Otto Kupfer, Piazza San Marco, ca 1935.